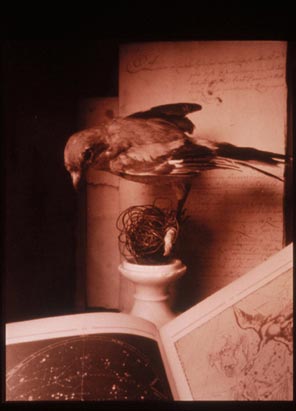

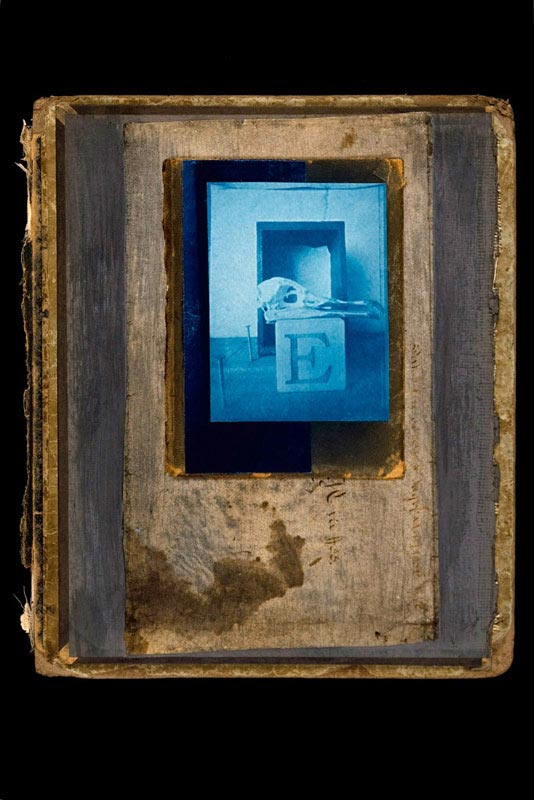

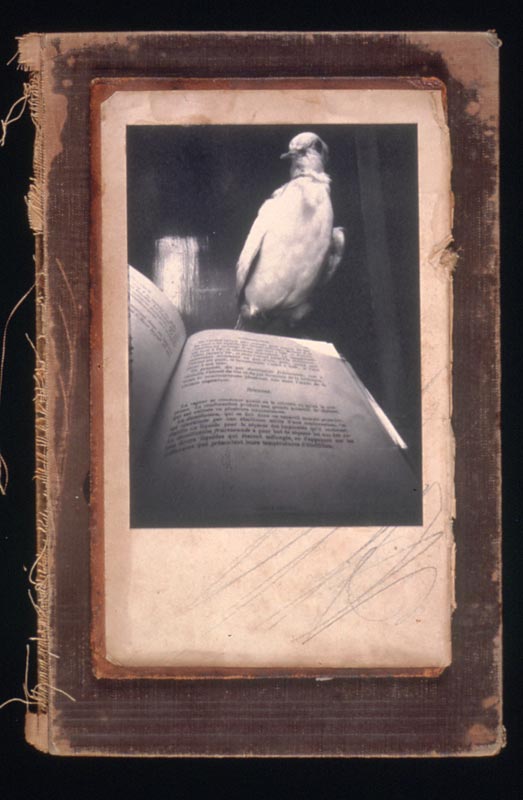

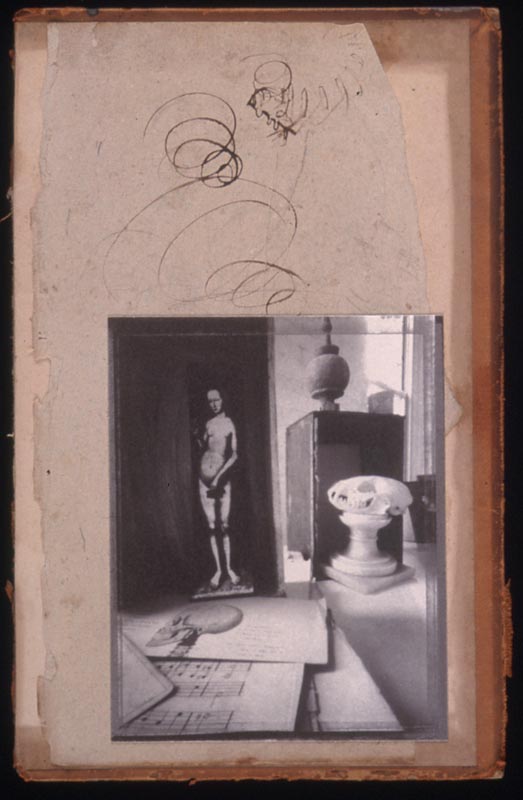

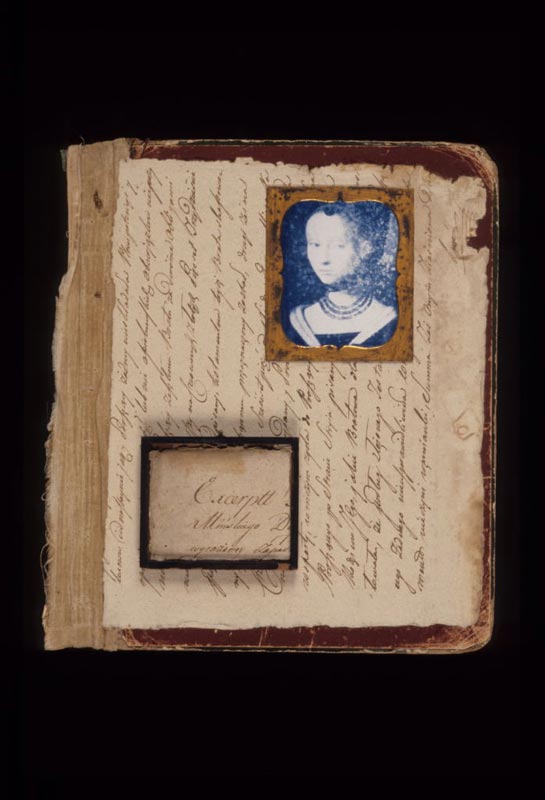

Back in 2008, I had the pleasure of meeting Jesseca Ferguson at the first f295 Seminar held at B&H in New York City. I was intrigued by her work which is as much collage and construction as pinhole imagery. Her images are seductive and richly layered, with items of the past interwoven with natural elements creating a story within the image. Blending polaroid with alternative processes, her images have a timeless quality to them — often reminescent of still life paintings.

Back in 2008, I had the pleasure of meeting Jesseca Ferguson at the first f295 Seminar held at B&H in New York City. I was intrigued by her work which is as much collage and construction as pinhole imagery. Her images are seductive and richly layered, with items of the past interwoven with natural elements creating a story within the image. Blending polaroid with alternative processes, her images have a timeless quality to them — often reminescent of still life paintings.

Without Lenses: When did you start making pinhole images?

Jesseca Ferguson: 1991

WL: Did you move into this from “traditional” photography or did you start with pinhole?

JF: I am not from a photo background and have never taken a photo course, per se. I come from a weaving/textiles, handmade paper, collage, drawing background. In the late 1980’s, I was using found photos (19th century) in my collages and got curious about ways I could make my OWN photos to incorporate into my collages.

As enlargers and all things photographic (lenses, light meters, F stops, etc.) made me nervous (they still do!), I wished to circumvent them somehow, yet still manage to make my own images.

That led me into a weekend workshop with Laura Blacklow (1990), where I was exposed to cyanotype and a few other handmade historic photo processes. A friend offered to show me how to develop 120 film (as I knew I needed negatives) and then I heard about pinhole cameras, which was a way to make BIG negatives (without an enlarger).

Hand-coating artist’s paper with a brush also appealed to me as I come from a fine arts background (drawing, collage, printmaking) and do not like the surface of silver gelatin paper as a collage element. I became intrigued with the idea of making large format images that could be contact printed with the sun (no enlarger!). Primitive pinhole cameras could be made at home for little or no money – no lens, no complications (or so I thought!). In 1991 I started working with orthochromatic film (relatively low cost, could be handled under a safelight) and an old typewriter case fashioned into a pinhole camera and have never regretted it.

Hand-coating artist’s paper with a brush also appealed to me as I come from a fine arts background (drawing, collage, printmaking) and do not like the surface of silver gelatin paper as a collage element. I became intrigued with the idea of making large format images that could be contact printed with the sun (no enlarger!). Primitive pinhole cameras could be made at home for little or no money – no lens, no complications (or so I thought!). In 1991 I started working with orthochromatic film (relatively low cost, could be handled under a safelight) and an old typewriter case fashioned into a pinhole camera and have never regretted it.

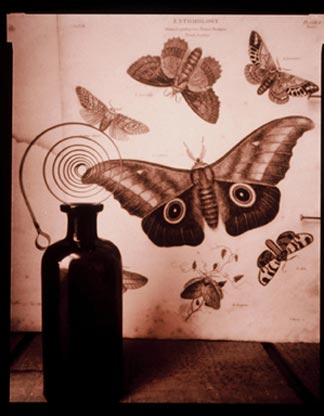

WL: You put together still-lifes to photograph – does historical painting influence your work?

JF: Good question – I am always looking at art history, either consciously or unconsciously – by looking at books, going to museums, having postcards of paintings on my studio walls. I especially love to look at work from the Northern Renaissance – Memling, van Eyck, Robert Campin (Master of Flémalle). Objects in these paintings had iconographic significance – a lily was not just a lily. (When I was in grad school (MFA 1986 Tufts University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), I was lucky enough to study medieval art history with Madeline Caviness and learned a lot from that experience.)

JF: Good question – I am always looking at art history, either consciously or unconsciously – by looking at books, going to museums, having postcards of paintings on my studio walls. I especially love to look at work from the Northern Renaissance – Memling, van Eyck, Robert Campin (Master of Flémalle). Objects in these paintings had iconographic significance – a lily was not just a lily. (When I was in grad school (MFA 1986 Tufts University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), I was lucky enough to study medieval art history with Madeline Caviness and learned a lot from that experience.)

I also look at photographers who arrange objects—Josef Sudek—also Fox Talbot’s early work. Additionally I like to go to old films (Fritz Lang, early Bergman, Cocteau & others) and sometimes think of my photographs as a still from some forgotten film.

WL: Your process also involves old books and book covers and making assemblages. This seems as much like sculpture as photography. Describe your process—when do the materials influence the image making and when does the image making define the materials?

WL: Your process also involves old books and book covers and making assemblages. This seems as much like sculpture as photography. Describe your process—when do the materials influence the image making and when does the image making define the materials?

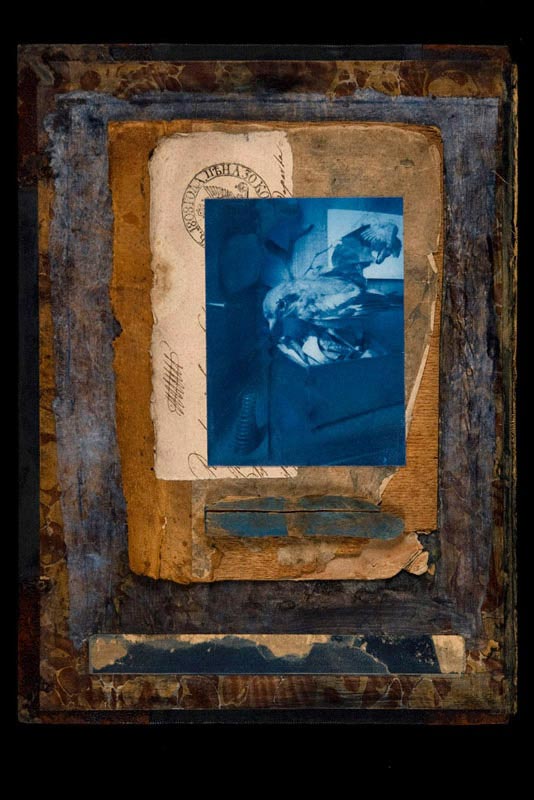

JF: Yes, I consider these collaged & assembled works to be “photo objects†rather than photographs per se. In that sense, they are akin to early photographs (ambrotypes, tintypes, daguerreotypes) with weight, and heft, in those ornate cases. I don’t usually make photographs to just be matted & framed – though sometimes that works out to be the case. I am not always satisfied with a framed, matted image as the final result – thus the collages.

About the relationship between materials and the image: there is sort of a dialogue in the process. Also, hunting for images and objects I can use—gathering and collecting in flea markets and old book shops—is very much part of my process. I believe that an object or old book finds me as much as I find it. I often pick something up and never know when, or even if, Iwill use it. Eventually, through trial and error, it may find a role as a prop in a photo or it may get glued down in a collage.

WL: You like to use some of the same elements over and over again. For example the little white bird – is there significance to this or does it just seem to happen?

JF: The white dove was purchased in 1998 at Deyrolle, the marvelously antiquated, but very expensive, taxidermy shop in Paris. (This shop is known to many thanks to the wonderful photographs Richard Ross made there, as seen in his book Museology.) While visiting Deyrolle, something prompted me to search for a bird (preferably white). I asked the saleslady “Est-ce que vous avez un oiseau un peu abîmé?†(“Do you have a slightly wrecked-up bird?â€) This dove miraculously was produced—quite battered with a broken tail, feathers in disarray, no perch—and thus affordable to me. I worked with him in Paris and back here in Boston. He made an excellent model for pinhole photography as he could hold a long pose (usually hours, using natural light), had a lively expression (despite being long dead!), and reflected light quite beautifully. He is still in my studio today, along with the books, objects, and other taxidermied specimens I use to make my (mostly pinhole) photographs.

JF: The white dove was purchased in 1998 at Deyrolle, the marvelously antiquated, but very expensive, taxidermy shop in Paris. (This shop is known to many thanks to the wonderful photographs Richard Ross made there, as seen in his book Museology.) While visiting Deyrolle, something prompted me to search for a bird (preferably white). I asked the saleslady “Est-ce que vous avez un oiseau un peu abîmé?†(“Do you have a slightly wrecked-up bird?â€) This dove miraculously was produced—quite battered with a broken tail, feathers in disarray, no perch—and thus affordable to me. I worked with him in Paris and back here in Boston. He made an excellent model for pinhole photography as he could hold a long pose (usually hours, using natural light), had a lively expression (despite being long dead!), and reflected light quite beautifully. He is still in my studio today, along with the books, objects, and other taxidermied specimens I use to make my (mostly pinhole) photographs.

WL: Does your work as an artist influence your teaching and your work as a curator?

WL: Does your work as an artist influence your teaching and your work as a curator?

JF: I think these 3 activities all go hand-in-hand. Teaching teaches me! Students are always teaching me things, whether by their inventions or reading or discoveries, or by the good questions they ask. Colleagues as well tell me about artists or books, new processes or materials. Teaching in an art school is terrific as I can attend lectures by visiting artists. Luckily I teach part-time, so I don’t get too bogged down by academic responsibilities. For my whole career I have been a “teaching nomad†– a footloose adjunct at various places, free to come & go. Also, I can only teach what I know –s o I am grateful to be able to work in art schools that accept my quirky blend of interests as valuable to their curriculum. A kind of “bricolage,†I guess – a notion or attitude very important to the artist – perhaps as valuable as specific knowledge of & expertise in certain techniques.

I have only curated 2 exhibitions – and they involved artists whose work I knew and loved, that I felt spoke well together. I think curating and teaching – like being an artist – are vital and important creative acts, requiring imagination, much-needed in today’s world. I think that teaching, curating, and making images/objects can all dovetail together. I especially love the idea of curating as way of communicating between cultures – as was possible with “Made in Poland: Contemporary Pinhole Photography†which fellow Boston-based pinhole photographer Walter Crump and I co-curated.

I have only curated 2 exhibitions – and they involved artists whose work I knew and loved, that I felt spoke well together. I think curating and teaching – like being an artist – are vital and important creative acts, requiring imagination, much-needed in today’s world. I think that teaching, curating, and making images/objects can all dovetail together. I especially love the idea of curating as way of communicating between cultures – as was possible with “Made in Poland: Contemporary Pinhole Photography†which fellow Boston-based pinhole photographer Walter Crump and I co-curated.

WL: Jesseca’s work can be seen as part of “American Metaphors: Seven American Pinhole Photographers” an exhibition currently traveling through Poland and at her website Museum of Memory.

Comments

1 Responses to “Collage, Construction and Pinhole: Making Memories with Jesseca Ferguson”

Your work is stunning, I love the various textures and medias used, it makes it so much more interesting than single media art. To me, it seems like it tells a story more than a 2 dimensional painting.